Effect of Stall Size, Number of Heat Lamps During Farrowing: Part 2

go.ncsu.edu/readext?820183

en Español / em Português

El inglés es el idioma de control de esta página. En la medida en que haya algún conflicto entre la traducción al inglés y la traducción, el inglés prevalece.

Al hacer clic en el enlace de traducción se activa un servicio de traducción gratuito para convertir la página al español. Al igual que con cualquier traducción por Internet, la conversión no es sensible al contexto y puede que no traduzca el texto en su significado original. NC State Extension no garantiza la exactitud del texto traducido. Por favor, tenga en cuenta que algunas aplicaciones y/o servicios pueden no funcionar como se espera cuando se traducen.

Português

Inglês é o idioma de controle desta página. Na medida que haja algum conflito entre o texto original em Inglês e a tradução, o Inglês prevalece.

Ao clicar no link de tradução, um serviço gratuito de tradução será ativado para converter a página para o Português. Como em qualquer tradução pela internet, a conversão não é sensivel ao contexto e pode não ocorrer a tradução para o significado orginal. O serviço de Extensão da Carolina do Norte (NC State Extension) não garante a exatidão do texto traduzido. Por favor, observe que algumas funções ou serviços podem não funcionar como esperado após a tradução.

English

English is the controlling language of this page. To the extent there is any conflict between the English text and the translation, English controls.

Clicking on the translation link activates a free translation service to convert the page to Spanish. As with any Internet translation, the conversion is not context-sensitive and may not translate the text to its original meaning. NC State Extension does not guarantee the accuracy of the translated text. Please note that some applications and/or services may not function as expected when translated.

Collapse ▲Data analysis reveals differences between gilts and multiparous sows in both behavior and productivity.

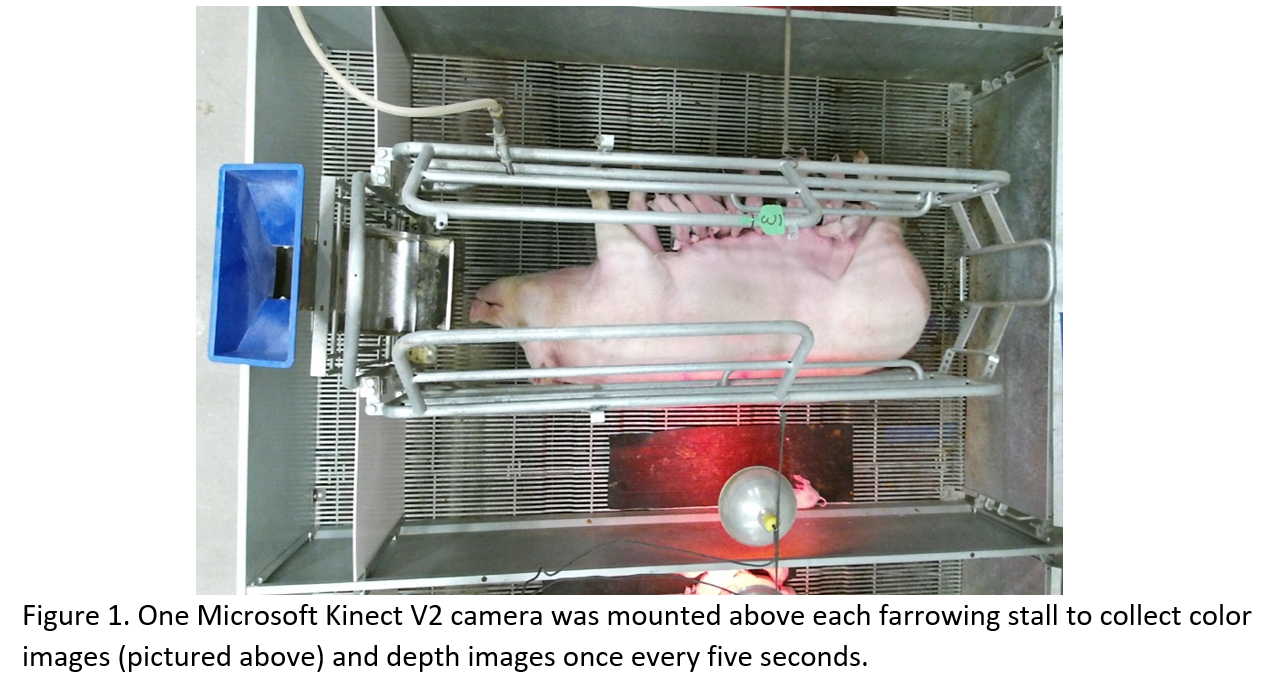

In addition to the productivity data collected for this large-scale field study comparing three farrowing stall layouts (TSL – traditional stall layout, ECSL – expanded creep stall layout, ESCSL – expanded sow and creep stall layout) and using one or two heat lamps (1HL or 2HL), sow and piglet behavior data were collected using a custom camera system (Leonard et al., 2019). One Microsoft Kinect V2 camera was mounted above each farrowing stall, approximately 8.4 feet above the floor. The Kinect camera provided a full top-down view of the sow stall and creep area below. Each camera collected one digital and depth image every five seconds (Figure 1). The depth images were later processed using an algorithm developed in MATLAB to classify the sow’s posture as sitting, standing, kneeling, or lying and behavior as feeding, drinking, or other. If the sow was lying down, the sow’s udder orientation was also classified. Sow posture data were analyzed from three days prior to farrowing to three days after farrowing, as well as days 7, 14, and 21 of lactation.

Sow Behavior Results

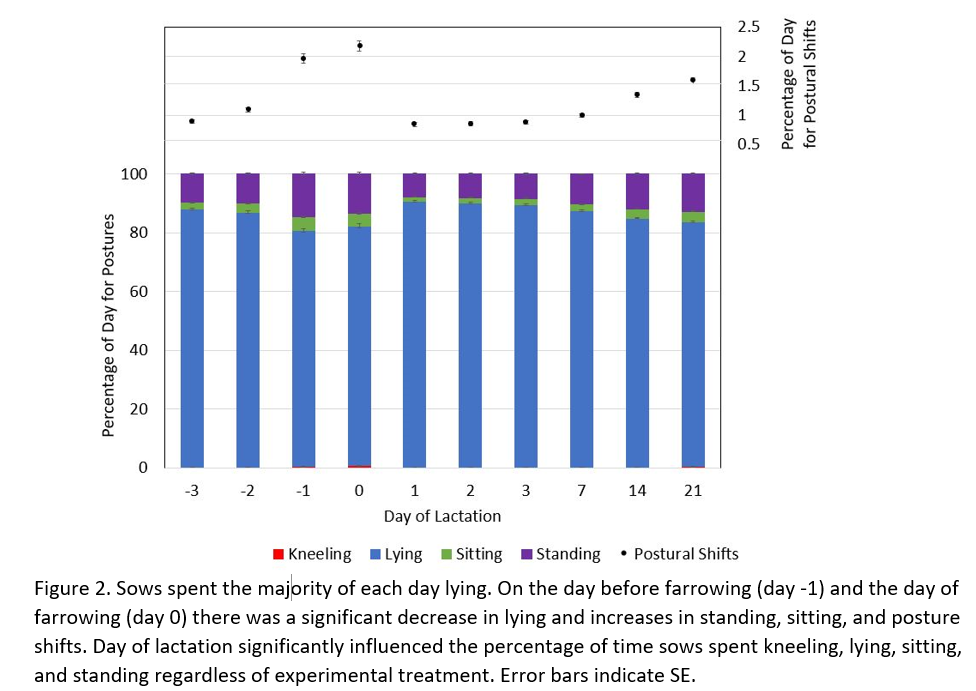

Overall, the sows spent the majority of each day lying, followed by standing, sitting, and kneeling (Figure 2). The percentage of day spent lying decreased on the day prior to farrowing (day -1) and day of farrowing (day 0) when the sows exhibited restlessness attributed to pre-farrowing nest-building behavior. On days -1 and 0 there was also a significant increase in the number of postural shifts. Then, the percentage of time lying increased to its highest levels on the day after farrowing. Lying gradually decreased throughout the course of lactation, which was expected as sows spend less time nursing as piglets become older.

The only treatment difference in sow posture was that sows in ESCSL spent on average 17 minutes more lying down than sows in ECSL and eight minutes less sitting than sows in ECSL and TSL. The change in sitting behavior is of particular interest, as it represents roughly a 20% decrease in time sitting. This suggests that the wider sow stall in the ESCSL improved sow comfort. Baxter and Edwards (2017) hypothesized that sows sit in farrowing stalls to mitigate interactions with their piglets, so the wider sow stall and creep area may have provided the sows with a greater sense of control over piglet interactions. Another potential reason for the decrease in sitting could be that in wider stalls the sows could more easily maneuver when changing posture from lying to standing, thus spending less time in the transitional posture of sitting.

When combining the sow behavior and productivity data, piglet pre-weaning mortality increased as sow lying increased, standing decreased, and time spent feeding decreased. Similar associations were seen when looking at specifically mortalities attributed to overlay. However, pre-weaning mortality, overlays, and all sow postures were strongly correlated with day of lactation. This indicates that mortality is more likely to be driven by age of piglet than sow postures. It is well documented that nearly 85% of pre-weaning mortalities occur in the first 48 hours after farrowing with most deaths attributed to a combination of chilling, malnutrition, and overlay, so it is unlikely that sow posture alone is the culprit.

The data analysis revealed differences between gilts and multiparous sows in both behavior and productivity. On average, gilts spent 10 minutes more per day lying compared to multiparous sows and less time feeding compared to parity two sows. Gilts had fewer piglets born alive than multiparous sows, but with a lower pre-weaning mortality, gilts weaned more piglets per litter than parity 4 sows. However, piglets reared by gilts had a lower individual piglet average daily weight gain. At the end of lactation, litters reared by gilts had more piglets with lower body weight than litters reared by multiparous sows.

The camera system used to monitor sow postures and behaviors was also used to record piglet location within the farrowing stalls. These results and their implications will be discussed in the third part of this series.

Sources

Baxter, E.M., Edwards, S.A., 2017. Piglet mortality and morbidity: inevitable or unacceptable? In: Spinka, M. (Ed.), Advances in Pig Welfare. Woodhead Publishing, Duxford, UK, p. 73-100.

Leonard, S.M., Xin, H., Brown-Brandl, T.M., Ramirez, B.C., Johnson, A.K., Dutta, S., Rohrer, G.A. (2021). Effects of farrowing stall layout and number of heat lamps on sow and piglet behavior. Applied Animal Behavior Science, 239(2021) 105334. doi: 10.1016/j.applanim.2021.105334

Leonard, S.M., Xin, H., Brown-Brandl, T.M., Ramirez, B.C., Dutta, S., Rohrer, G.A. (2020). Effects of farrowing stall layout and number of heat lamps on sow and piglet productivity. Animals. 10(2):348. doi: 10.3390/ani10020348

Leonard, S.M., Xin, H., Brown-Brandl, T.M., Ramirez, B.C. (2019). Development and application of an image acquisition system for characterizing sow behaviors in farrowing stalls. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture. doi: 10.1016/j.compag.2019.104866